I started this blog in May, in part to occupy my time during the Covid-19 lockdown. But I was also motivated by a growing dissatisfaction with the quality of data analysis I was witnessing in climate science, and in particular the lack of any objectivity in the way much of the data was being presented and reported. My concerns were twofold.

The first was the drip-drip of selective alarmism with an overt confirmation bias that kept appearing in the media with no comparable reporting of events that contradicted that narrative. The worry here is that extreme events that are just part of the natural variation of the climate were being portrayed as the new normal, while events of the opposite extreme were being ignored. It appeared that balance was being sacrificed for publicity.

The second was the over-reliance of much of the climate analysis on complex statistical analysis techniques of doubtful accuracy or veracity. To paraphrase Lord Rutherford: if you need to use complex statistics to see any trends in your data, then you would be better off using better data. Or to put it more simply, if you can't see a trend with simple regression analysis, then the odds are there is no trend to see.

The purpose of this blog has not been to repeat the methods of climate scientists, nor to improve on them. It has merely been to set a benchmark against which their claims can be measured and tested.

My first aim has been to go back to basics, to examine the original temperature data, look for trends in that data, and to apply some basic error analysis to determine how significant those trends really are. Then I have sought to compare what I see in the original data with what climate scientists claim is happening. In most cases I have found that the temperature trends in the real data are significantly less than those reported by climate scientists. In other words, much of the reported temperature rises, particularly in Southern Hemisphere data, result from the data manipulations performed by the climate scientists on the data. This implies that many of the reported temperature rises are an exaggeration.

In addition, I have tried to look at the physics and mathematics underpinning the data in order to test other possible hypotheses that could explain the observed temperature trends that I could detect. Below I have set out a summary of my conclusions so far.

1) The physics and mathematics

There are two alternative theories that I have considered as explanations of the temperature changes. The first is natural variation. The problem here is that in order to conclusively prove this to be the case you need temperature data that extends back in time for dozens of centuries, and we simply do not have that data. Climate scientists have tried to solve this by using proxy data from tree rings and sediments and other biological or geological sources, but in my opinion these are wholly inadequate as they are badly calibrated. The idea that you can measure the average annual temperature of an entire region to an accuracy of better than 0.1 °C simply by measuring the width of a few tree rings, when you have no idea of the degree of linearity of your proxy, or the influence of numerous external variables (e.g. rainfall, soil quality, disease, access to sunlight), is preposterous. But there is another way.

i) Fractals and self-similarity

If you can show that the fluctuations in temperature over different timescales follow a clear pattern, then you can extrapolate back in time. One such pattern is that resulting from fractal behaviour and self-similarity in the temperature record. By self-similarity I mean that every time you average the data you end up with a pattern of fluctuations that looks similar to the one you started with, but with amplitudes and periods that change according to a precise mathematical scaling function.

In Post 9 I applied this analysis to various sets of temperature data from New Zealand. I then repeated it for data from Australia and then again in Post 42 for data from De Bilt in the Netherlands. In virtually all these cases I found a consistent power law for the scaling parameter indicative of a fractal dimension of between 0.20 and 0.30, with most values clustered close to 0.25. The low magnitude of this scaling term suggests that the fluctuations in long term temperatures are much greater in amplitude than conventional statistical analysis would predict.

For example, in the case of De Bilt it suggests that the standard deviation in the average 100-year temperature is more than 0.2 °C. This means that there is a 16% probability of the mean temperature for any century being more than 0.3°C more (or less) than the mean temperature for the previous century, and therefore a one in six possibility of a 0.6 °C temperature rise in any given century. So a 0.6 °C temperature rise over a century could occur once every 600 years purely because of natural variations in temperature. It also suggests that similar temperature variations that we have seen in temperature data in the last 50 or 100 years might have been repeated frequently in the not so distant past.

ii) Direct anthropogenic surface heating (DASH) and the urban heat island (UHI)

Another possible explanation for any observed rise in temperature is the heating of the environment that occurs due to human industrial activity. All energy use produces waste heat. Not only that, but all energy must end up as heat and entropy in the end. The Second Law of Thermodynamics tells us that. It is therefore inevitable that human activity must heat the local environment. The only question is by how much.

Most discussions in this area focus on what is known as the urban heat island (UHI). This is a phenomenon whereby urban areas either absorb extra solar radiation because of changes made to the surface albedo by urban development (e.g. concrete, tarmac, etc), or tall buildings trap the absorbed heat and reduce the circulation of warm air, thereby concentrating the heat. But there is another contribution that continually gets overlooked - direct anthropogenic surface heating (DASH).

When humans generate and consume energy they liberate heat or thermal energy. This energy heats up the ground, and the air just above it, in much the same way that radiation from the Sun does. In so doing DASH adds to the heat that is re-emitted from the Earth's surface, and therefore increases the Earth's surface temperature at that location.

In Post 14 I showed that this heating can be significant - up to 1 °C in countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands with high levels of economic output and high population densities. In Post 29 I extended this idea to look at suburban energy usage and found a similar result.

What this shows is that you don't need to invoke the Greenhouse Effect to find a plausible mechanism via which humans are heating the planet. Simple thermodynamics will suffice. Of course climate scientists dismiss this because they assume that this heat is dissipated uniformly across the Earth's surface - but it isn't. And just as significant is the fact that the majority of weather stations are in places where most people live, and therefore they also tend to be in regions where the direct anthropogenic surface heating (DASH) is most pronounced. So this direct heating effect is magnified in the temperature data.

iii) The data reliability

It is taken as read that the temperature data used to determine the magnitude of the observed global warming is accurate. But is it? Every measurement has an error. In the case of temperature data it appears that these errors are comparable in magnitude to many of the effects climate scientists are trying to measure.

In Post 43 I looked at pairs of stations in the Netherlands that were less than 1.6 km apart. One might expect that most such pairs would exhibit identical datasets for the two stations in the pair, but they don't. In virtually every case the fluctuations in the difference in their monthly average temperatures was about 0.2 °C. While this was consistent with the values one would expect based on error analysis, it does highlight the limits to the accuracy of this data. It also raises questions about how valid techniques such as breakpoint adjustment are, given that these techniques depend on detecting relatively small differences in temperature for data from neighbouring stations.

iv) Temperature correlations between stations

In Post 11 I looked at the product moment correlation coefficients (PMCC) between temperature data from different stations, and compared the correlation coefficients with the station separation. What became apparent was evidence for a strong negative linear relationship between the maximum correlation coefficient for temperature anomalies between pairs of station and their separation. For station separations of less than 500 km positive correlations of better than 0.9 were possible, but this dropped to a maximum correlation of about 0.7 for separations of 1000 km and 0.3 at 2000 km.

There were also clear differences between the behaviour of the raw anomaly data and the Berkeley Earth adjusted data. The Berkeley Earth adjustments appear to reduce the scatter in the correlations for the 12-month averaged data, but do so at the expense of the quality of the monthly data. This suggests that these adjustments may be making the data less reliable not more so. The improvement in the scatter of the Berkeley Earth 12-month averaged data is also curious. Is it because it is this data that is used to determine the adjustments and not the monthly data, or is this not the case and instead there is some other reason? And what of the scatter in the data? Can we use this to measure the quality and reliability of the original data? This clearly warrants further study.

Fig. 45.1: Correlations (PMCC) for the period 1971-2010 between

temperature anomalies for all stations in New Zealand with a minimum

overlap of 200 months. Three datasets were studied: a) the monthly anomalies; b) the 12-month average of the monthly anomalies; c) the 5-year average of the monthly anomalies. Also studied were the equivalent for the Berkeley Earth adjusted data.

2) The data

Over the last eight months I have analysed most of the temperature data in the Southern Hemisphere as well as all the data in Europe that predates 1850. The results are summarized below.

i) Antarctica

In Post 4 I showed that the temperature at the South Pole has been stable since the 1950s. There is no instrumental temperature data before 1956 and there are only two stations of note near the South Pole (Amundsen-Scott and Vostok). Both show stable or negative trends.

Then in Post 30 I looked at the temperature data from the periphery of the continent. This I divided into three geographical regions: the Atlantic coast, the Pacific coast and the Peninsula. The first two only have data from about 1950 onwards. In both cases the temperature data is also stable with no statistically significant trend either upwards or downwards. Only the Peninsula exhibited a strong and statistically significant upward trend of about 2 °C since 1945.

ii) New Zealand

Fig. 45.2: Average warming trend of for long and medium stations in New Zealand. The best fit to the data has a gradient of +0.27 ± 0.04 °C per century.

In Posts 6-9 I looked at the temperature data from New Zealand. Although the country only has about 27 long or medium length temperature records, with only ten having data before 1880, there is sufficient data before 1930 to suggest temperatures in this period were almost comparable to those of today. The difference is less than 0.3 °C.

iii) Australia

Fig. 45.3: The temperature trend for Australia since 1853. The best

fit is applied to the interval 1871-2010 and has a gradient of 0.24 ±

0.04 °C per century.

The temperature trend for Australia (see Post 26) is very similar to that of New Zealand. Most states and territories exhibited high temperatures in the latter part of the 19th century that then declined before increasing in the latter quarter of the 20th century. The exceptions were Queensland (see Post 24) and Western Australia (see Post 22), but this was largely due to an absence of data before 1900. While there is much less temperature data for Australia before 1900 compared to the latter part of the 20th century, there is sufficient to indicate that, as in New Zealand, temperatures in the late 19th century were similar to those of the present day.

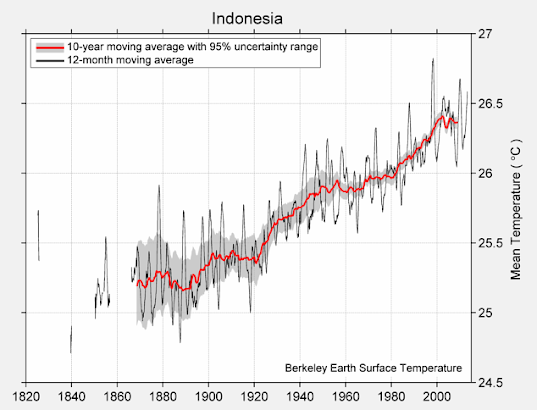

iv) Indonesia

Fig. 45.4: The temperature trend for Indonesia since 1840. The best

fit is applied to the interval 1908-2002 and has a negative gradient of -0.03 ±

0.04 °C per century.

The temperature data for Indonesia is complicated by the lack of quality data before 1960 (see Post 31). The temperature trend after 1960 is the average of between 33 and 53 different datasets, but between 1910 and 1960 it generally comprises less than ten. Nevertheless, this is sufficient data to suggest that temperatures in the first half of the 20th century were greater than those in the latter half. This is despite the data from Jakarta Observatorium which exhibits an overall warming trend of nearly 3 °C from 1870 to 2010 (see Fig. 31.1 in Post 31).

It is also worth noting that the temperature data from Papua New Guinea (see Post 32) is similar to that for Indonesia for the period from 1940 onwards. Unfortunately Papua New Guinea only has one significant dataset that predates 1940, so conclusions regarding the temperature trend in this earlier time period are difficult to ascertain.

v) South Pacific

Most of the temperature data from the South Pacific comes from the various islands in the western half of the ocean. This data exhibits little if any warming, but does exhibit large fluctuations in temperature over the course of the 20th century (see Post 33). The eastern half of the South Pacific, on the other hand, exhibits a small but discernible negative temperature trend of between -0.1 and -0.2 °C per century (see Post 34).

vi) South America

Fig. 45.5: The temperature trend for South America since 1832. The best

fit is applied to the interval 1900-1999 and has a gradient of +0.54 ±

0.05 °C per century.

In Post 35 I analysed over 300 of the longest temperature records from South America, including over 20 with more than 100 years of data. The overall trend suggests that temperatures fluctuated significantly before 1900 and have risen by about 0.5 °C since. The high temperatures seen before 1850 are exclusively due to the data from Rio de Janeiro and so may not be representative of the region as a whole.

vii) Southern Africa

Fig. 45.6: The temperature trend for South Africa since 1840. The

best fit is applied to the interval 1857-1976 and has a gradient of

+0.017 ± 0.056 °C per century.

In Posts 37-39 I looked at the temperature trends for South Africa, Botswana and Namibia. Botswana and Namibia were both found to have less than four usable sets of station data before 1960 and only about 10-12 afterwards. South Africa had much more data, but the general trends were the same. Before 1980 the temperature trends were stable or perhaps slightly negative, but after 1980 there was a sudden rise of between 0.5 °C and 2 °C in all three trends, with the largest being found in Botswana. This does not correlate with accepted theories on global warming (the rises in temperature are too large and too sudden, and do not correlate with rises in atmospheric carbon dioxide), and so the exact origin of these rises appears to be unexplained.

viii) Europe

Fig. 45.7: The temperature trend for Europe since 1700. The best fit

is applied to the interval 1731-1980 and has a positive gradient of

+0.10 ± 0.04 °C per century.

In Post 44 I used the 109 longest temperature records to determine the temperature trend in Europe since 1700. The resulting data suggests that temperatures were stable from 1700 to 1980 (they rose by less than 0.25 °C), and then rose suddenly by about 0.8 °C after 1986. The reason for this change is unclear, but one possibility is that it has occurred due to a significant improvement in air quality that reduced the amount of particulates in the atmosphere. These particulates, that may have been present in earlier years, could have induced a cooling that compensated for the underlying warming trend. Once removed, the temperature then rebounded. Even if this is true, it suggests a maximum warming of about 1 °C since 1700, much of which could be the result of direct anthropogenic surface heating (DASH) as discussed in Post 14. In countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands the temperature rise is even less than that expected from such surface heating. It is also much less than that expected from an enhanced Greenhouse Effect due to increasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere (i.e. about 1.5 °C in the Northern Hemisphere since 1910). In fact the total temperature rise should exceed 2.5 °C. So here is the BIG question? Where has all that missing temperature rise gone?