The South Pacific is too large to consider in one discussion, and its weather stations are not evenly distributed. The map below indicates the location of all the long stations (≥ 1200 months of data) and medium stations (480 - 1199 months). It can be seen that the majority of stations are in the western half of the ocean, to the west of the Pitcairn Islands (see the central cross to the right of French Polynesia in Fig. 33.1 below).

Fig. 33.1: The locations of all the long and medium stations in the South Pacific by country.

Overall there are only six long stations, four to the west of Pitcairn Island and two on Isla Juan Fernandez off the coast of Chile. In addition, there are 60 medium stations, of which only five are either on, or to the east of, the Pitcairn Islands (longitude 130.1°W). Of these 66 stations, 41 can be classified as having warming trends where the temperature trend is positive and exceeds twice the uncertainty in the trend (see Fig. 33.2 below).

Fig. 33.2: The locations of long stations (large squares) and medium stations (small diamonds) in the South Pacific. Those stations with a high warming trend are marked in red.

In this post I will look at the temperature records in the western half of the South Pacific (west of longitude 132°W). This will also include a couple of stations in Kiribati that are just north of the equator, but will exclude the Pitcairn Islands and the islands off the coast of South America.

The total number of station temperature records in this region is more than 100, but only 59 have more than 480 months of data, and only four of those are long stations. Averaging the anomalies from these 59 records results in the temperature trend shown below in Fig. 33.3.

Fig. 33.3: The temperature trend for the western South Pacific since 1860. The best fit is applied to the interval 1912-1999 and has a gradient of 0.18 ± 0.04 °C per century. The temperature changes are relative to the 1961-1990 average.

The anomaly data in Fig. 33.3 was calculated by finding the monthly reference temperature (MRT) for the period 1961-1990 for each record, and subtracting it from the raw data to determine the temperature anomaly (see Post 4 for details). The anomalies for each month were then averaged.

Only records that had a minimum of 40% of data within this time-frame for any of the twelve months of the year January-December were included in the average for that month. Of the 59 records, one had no qualifying months and two had only nine months out of the possible twelve that satisfied this criterion. Thus one was excluded completely and two were only included for the nine months that their MRTs were valid. The resulting mean temperature trend is illustrated above.

Although the temperature data in Fig. 33.3 has an upward or warming trend from about 1900 onwards, it is very modest (0.18 °C per century for 1912-1999), and it is much less than the fluctuations in the 5-year moving average. The warming is therefore not statistically significant, particularly when compared to the variations in temperature seen before 1895. It should be noted, though, that the data before 1895 is based on only one or two records at most for that time period.

Fig. 33.4: Temperature trends for all long and medium stations in the western South Pacific since 1860 derived by aggregating and averaging the Berkeley Earth adjusted data. The best fit linear trend line (in red) is for the period 1912-1999 and has a gradient of +0.83 ± 0.02 °C/century.

The data in Fig. 33.3 is interesting, but it is meaningless unless we can test it against known control. That control is the equivalent data based on Berkeley Earth adjusted anomalies. This is shown in Fig. 33.4 above. Once again this data exhibits the standard rise in temperature since 1900 of about 1 °C that the IPCC and the climate science community insist we should see. The problem is, that once again, the majority of this warming comes not from the real data, but from the adjustments made to it (see Fig. 33.5 below). As I have noted before, these adjustments are derived from two separate sources: (i) homogenization of the data when constructing the MRTs; (ii) breakpoint adjustments made to different parts of each data set in order to improve the data fitting.

Fig. 33.5: The contribution of Berkeley Earth (BE) adjustments to the anomaly data after smoothing with a 12-month moving average. The linear best fit to the data is for the period 1912-1999 (red line) and the gradient is +0.65 ± 0.03 °C per century. The orange curve represents the contribution made to the BE adjustment curve by breakpoint adjustments only.

Conclusions

1) There is no evidence of a strong warming trend in the aggregated western South Pacific raw temperature anomaly data (see Fig. 33.3).

2) Over 78% of the warming seen in the aggregated Berkeley Earth adjusted data (see Fig. 33.4) is due to adjustments made to the data (see Fig. 33.5), and most of this comes from breakpoint adjustments.

Addendum

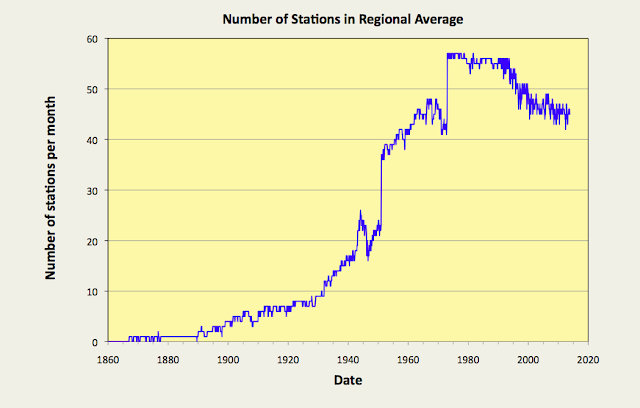

The maximum number of temperature records included in the trend in Fig. 33.3 is 57. Between 1900 and 1950 this increases from only 4 to about 24 (see Fig. 33.6 below). The other point to note is that the standard deviation of the temperature fluctuations for most stations in the region is only about 0.5 °C (compared to over 1 °C for most of Australia and New Zealand, for example). This means that the error in the mean temperature trend in Fig. 33.3 is less than 0.08 °C after 1950, but for the period 1900-1950 it varies from approximately 0.25 °C to 0.10 °C. All these uncertainties are, however, much less than the apparent random variations seen in the 5-year moving average for the mean temperature trend. This suggests that the fluctuations seen in the mean temperature trend from 1900-2013 are not the result of a lack of data in the first half of the 20th century or bad data. They are real and indicate the natural behaviour of the temperature record over timescales exceeding 100 years.

Fig. 33.6: The number of sets of station data included each month in the temperature trend for South Pacific (West) shown in Fig. 33.3.

No comments:

Post a Comment