In my previous post I showed how Schwarzschild's equation for the absorption and emission of radiation by a gas could result in identical results to a model based purely on elastic scattering. The only conditions on the proof I presented were that the gas is only heated at one end, and that energy conservation applies within the gas; namely that the energy each layer of the gas emits by Planck radiation balances the total energy it absorbs from the two fluxes of upwelling and downwelling radiation, Iu(x) and Id(x) respectively. I then showed that this leads to a higher transmission through thick layers of greenhouse gas than would be expected based on the Beer-Lambert law.

In this post I will consider two other situations; one where the gas is heated equally at both ends of a long column, and the second where the gas is heated at the bottom and its concentration decreases exponentially with height. The first is analogous to the situation in Antarctica, while the second is a good approximation of how the Greenhouse Effect works on both Earth and Mars.

1) Heating a column of gas at both ends

In Post 91 I showed in Fig. 91.3 how the intensity of radiation travelling in the forward and reverse directions through a greenhouse gas changes with distance into the gas when the gas is heated at one end. In both cases the radiation flow decreases linearly with distance into the gas, with the difference in the forward and reverse fluxes remaining constant. This difference in fluxes decreases with gas concentration and the thickness of the gas layer as illustrated in Fig. 91.4. But suppose the layer of gas is instead heated equally at both ends? What will happen then?

Well the resulting energy flows can be deduced from Fig. 91.3 using a combination of reflection symmetry and superposition and are shown in Fig. 92.1 below.

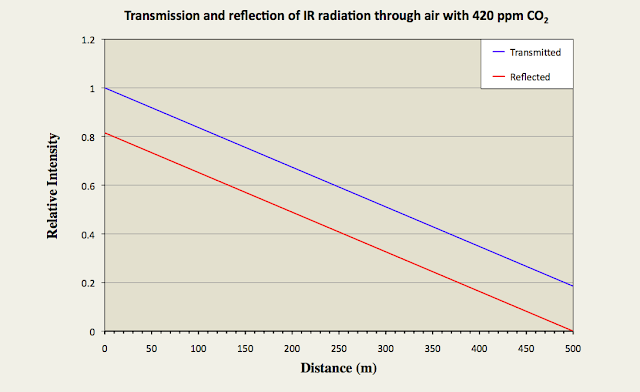

Fig. 92.1: The relative intensities of transmitted and reflected radiation in a 500 m long column of air with 420 ppm CO2 that is heated equally from both ends. LT is radiation transmitted from left to right when the heating is at x = 0 m, and LR is the amount reflected. RT is radiation transmitted from right to left when the heating is at x = 500 m, and RR is the amount reflected.

In Fig. 92.1 the curve TL (blue curve) represents the radiation incident from the left at x = 0 m which is then partially reflected by the greenhouse gas to create a reflected flux RL (red curve) that propagates from right to left, building in strength as it propagates. This much is identical to the situation in Fig. 91.3 in the previous post. However, in the case of Fig. 92.1 an identical radiation flux RT also enters the column of gas from the right (green curve). This is also partially reflected by the greenhouse gas to create a reflected flux RR (violet curve) that propagates from left to right. The net result is that there are now two radiation fluxes travelling from left to right (TL and RR), and two travelling in the opposite direction (LR and RT).

It can then be seen that the total radiation flowing from left to right will be the sum of LT and RR, which will be a constant value of 1.0 at all points along the gas column. The same is true for the total radiation flowing from right to left. In other words, the radiation that is emitted at the right hand exit of the column (x = 500 m) balances exactly the energy that entered initially at x = 0 m. Similarly the radiation that is emitted at the left hand exit of the column (x = 0 m) exactly balances the energy that initially entered at the right (at x = 500 m). This result leads to three important conclusions.

The first is that in this situation the gas must be isothermal. This follows from the Schwarzschild's equation (see Eq. 91.6 in Post 91). As the total radiation flux in both directions is constant, it follows that the differentials of both Iu(x) and Id(x) must be zero and so the following equality must hold at all points x.

Iu(x) = Id(x) = B(λ,T)

(92.1)

As Iu(x) and Id(x) are both independent of x, then it follows that B(λ,T) must be as well. In which case the temperature T must be independent of x.

The second is that the radiation emitted at each end of the column in not just the radiation that entered at the opposite end. Some of it is radiation that has been reflected by the greenhouse gases via the Greenhouse Effect. This is an important point that is lost on many. It is often falsely claimed that because the gas is isothermal and the radiation flux exiting the gas balances that entering at the opposite end, then this must mean that the Greenhouse Effect is not in operation. Actually it is. It just appears not to be.

The third conclusion is that the Beer-Lambert law cannot be valid in this situation as it cannot explain this result. If the transmitted radiation fluxes LT and RT obeyed the Beer-Lambert law then they would both decay exponentially with distance into the gas, and so too would their reflected fluxes LR and RR. This would mean that the total flux in each direction at the centre of the gas column would be less than at the ends. The laws of thermodynamics cannot allow this to happen as it would lead to a permanent temperature decrease from each end towards the centre. Energy would flow into the centre only to disappear there in violation of the law of conservation of energy. So the Beer-Lambert law is a red herring in this instance.

2) The Greenhouse Effect for Earth's atmosphere

The Earth's atmosphere deviates from the examples I have discussed so far in one major respect: its density, n(x), decreases with height, x. This density change is more or less exponential over most of the lowest 80 km and is of the form

n(x) = no e-kx

(92.2)

where k = 0.15 km-1. As the relative concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2)in the atmosphere is remarkably constant at about 420 ppm for all altitudes up to at least 80 km, it then follows that the CO2 density will also decay with altitude, x, in accordance with Eq. 92.2 as well with no = 0.018 mol/m3. As the atmosphere is mainly heated from the bottom by the Earth's surface this decrease in density with height will significantly effect the nature of the Greenhouse Effect.

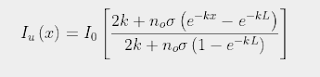

The strength of the Greenhouse Effect can be determined by substituting the expression for n(x) shown in Eq. 92.2 into Eq. 91.5 in Post 91. It is then possible to solve for Iu(x) subject to the constraint that the difference between Iu(x) and Id(x) remains constant for all values of x due to conservation of energy as I explained in Post 88. The result is that Iu(x) varies with x as

(92.3)

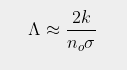

where σ is the absorption/emission cross-section of the CO2 molecules and L is the total height of the atmosphere. It then follows (by setting x = L in Eq. 92.3) that the total amount of radiation emitted at the top of the atmosphere into outer space will be ΛIo where the emitted fraction Λ is given by

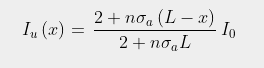

Subtracting ΛIo from Eq. 92.3 then gives the associated expression for the downwelling radiation

As the height of the atmosphere, L, exceeds 80 km, and k is much smaller than noσ, it can then be seen that Eq. 92.4 will approximate as

(92.6)

This is virtually identical to the result shown in Eq. 91.10 in Post 91, but with L replaced by 1/k. This is not very surprising as the mathematics of integral calculus tells us that 1/k is the effective thickness of an atmosphere that gets exponentially thinner with increasing height. It also indicates that the amount of radiation that escapes at the top of the atmosphere will decrease inversely (i.e. reciprocally) with CO2 concentration and not exponentially as predicted by the Beer-Lambert law. This is shown graphically in Fig. 92.2 below where Iu(x) based on Eq. 92.3 at each altitude x is compared to the expected transmission based on the Beer-Lambert law. The difference is striking.

What Fig. 92.2 shows is that the amount of 15 µm radiation escaping at the top of the atmosphere is much greater than many people think. According to the Beer-Lambert law it should be so low as to be unmeasurable. In reality it could be as much as 1.5%. The blue curve in Fig. 92.2 does fall exponentially, but not to zero: it tends asymptotically to Λ. The value of Λ also depends on the nature of the atmosphere as Eq. 92.4 shows. However, its dependence on CO2 concentration is reciprocal not exponential. This is why more radiation escapes than many people intuitively think can do.

Summary

The examples outlined in this post show that the Greenhouse Effect is more complex than the simplistic model that is generally presented. Even thick layers of greenhouse gas will emit appreciable amounts of infra-red radiation from within their absorption bands. Relying on the Beer-Lambert law will result in at best an incomplete picture, and at worst a totally misleading one.

Yes, the amount of IR radiation transmitted by the Earth's atmosphere reduces exponentially with height, at least at lower altitudes, but this is not due to its absorbing properties associated with the Beer-Lambert law. It is due primarily to the exponential drop in CO2 concentration with height. Even then this exponential fall never tends to zero as Eq. 92.3 and Eq. 93.4 demonstrate, but instead tend to a finite transmission value Λ that could be as much as 1.5%.