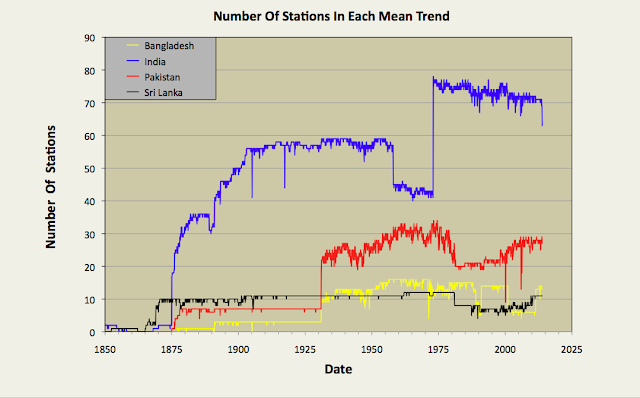

In my previous four blog posts I determined the temperature trends for India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh using unadjusted temperature data. The number of stations used to calculate the mean temperature each month is shown in Fig. 75.1 below. In the first three cases no warming was detectable before 1975, and only a modest temperature increase of about 0.6°C thereafter. In the case of Bangladesh there was a continuous warming that amounted to less than 0.3°C. This is significantly different from the conventional narrative on global warming, and highlights the impact that temperature adjustments have on the warming trends published by most of the main climate groups. In almost all cases the affect of these adjustments is to increase the rate of warming in the final trend as most of the regional trends I have published on this blog have also illustrated. In this post I will combine the results for India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh into a temperature trend for the region.

Fig. 75.1: The number of station records included each month in the mean temperature anomaly for each of four countries in South Asia.

In Post 70 I performed a similar task for data from the different countries in South-East Asia using two separate methods. One method just involved a simple average of temperature anomalies from all the different stations in the region, while the second used a weighting process that was used to average the mean anomalies for the different countries based on their land areas. If all the countries have similar densities of stations, then both methods should yield the same result. In the case of South-East Asia that was broadly the case for most countries other than Burma, but the differences in the two methods still led to a difference in the temperature trend gradients of almost 0.1°C per century. In the case of South Asia there are large differences in station density between countries, and these differences can also change over time, as shown in Fig. 75.2 below. For this reason, in this post I have chosen to adopt the area weighted method to determine the regional temperature trend.

Fig. 75.2: The station density each month for each of four countries in South Asia.

By comparing Fig. 75.1 and Fig. 75.2 it can be seen that India clearly has the most sets of station data, but it is Sri Lanka that has the highest density of stations. However, the temperature anomaly for Sri Lanka will also be subject to greater uncertainty as it is based on only a handful of stations (eleven at most). Then again, the contribution of the Sri Lanka stations to the final regional trend will be small due to the much smaller area of Sri Lanka compared to both India and Pakistan.

Fig. 75.3: The temperature trend for South Asia based on an average of anomalies from all long and medium stations. The best fit is applied to the monthly mean data from 1876 to 1975 and has a positive gradient of +0.19 ± 0.06 °C per century. The monthly temperature changes are defined relative to the 1951-1980 monthly averages.

Applying an area weighted approach to the calculation results in the temperature anomaly time series shown in Fig. 75.3 above. This is calculated by multiplying the mean anomaly data for each country (e.g. the monthly data in Fig. 74.2 for Bangladesh) by the area of that country, and then summing the resulting products for all four countries in the region. Then the result is divided by the total area of the four countries.

Like the equivalent anomaly time series for the individual countries, the regional anomaly exhibits very little warming before 1975 with about 0.5°C of warming occurring thereafter (see Fig. 75.3). To reiterate, this is the result that we get when we use the actual raw unadjusted temperature data for each station and not the adjusted/homogenized data that is generally favoured by climate scientists.

Fig. 75.4: Temperature trends for South Asia based on an average of Berkeley Earth adjusted data from all long and medium stations. The best fit linear trend line (in red) is for the period 1876-2005 and has a gradient of +0.66 ± 0.02°C/century.

If, however, we perform the same calculation with adjusted data (which is available in the same data file as the unadjusted data on the Berkeley Earth site) we get a quite different result as is shown in Fig. 75.4 above. There is now a strong and continuous warming trend from 1875 onwards. The total warming is claimed to be 1.25°C, with 0.5°C of this occurring before 1975 (see 10-year average in Fig. 75.4). This is still less than that claimed by Berkeley Earth and shown in Fig. 75.5 below. However, this is likely to be because Berkeley Earth included both Iran and Afghanistan in the Southern Asia region, and according to Berkeley Earth the regional temperature trends for both Iran and Afghanistan exhibit over 1.5°C of warming after 1970. That would help to explain the larger temperature rise post-1970 seen in Fig. 75.5 (almost 1°C) than is seen in Fig. 75.4 (only 0.7°C). What is harder to explain is why there is so much warming before 1900 in Fig. 75.5 when there is a) so little data with almost all being due to one or two stations in India, and b) very little increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels to cause such a temperature increase.

Fig. 75.5: The temperature trend for South Asia since 1790 according to Berkeley Earth.

Finally, if we compare the temperature trends for the four countries of South Asia we see that while there are broad similarities in their general trends over timescales of decades, there is only moderate correlation of more short term features and fluctuations (see fig. 75.6 below). The main reason for this is distance. The principal cities of Bangladesh (Dhaka), Sri Lanka (Colombo) and Pakistan (Karachi) are all at least 2000 km apart. As I demonstrated in Post 11, temperature anomaly time series from stations that are more than 1500 km apart are very poorly correlated as Fig. 11.2(a) in that post illustrates.

Fig. 75.6: A comparison of the temperature trends of Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka with that of neighbour India. For clarity the trends for Pakistan and Bangladesh are offset by +1°C and -1°C respectively.

Summary

The temperature trend for Southern Asia shows no warming before 1975 and only about 0.5°C thereafter (see Fig. 75.3).

The trend based on Berkeley Earth adjusted data shows significantly more warming (about 1.1°C in total), including significant warming (about 0.5°C) before 1975 (see Fig. 75.4).

No comments:

Post a Comment