There are two major problems when it comes to analysing the temperature data of Ecuador. The first is that there is very little good data. The second is that what data there is is subject to major natural variations; not least from El Niño.

In total there are only six medium stations in Ecuador with more than 480 months of data and only one with more than 800 months of data. That station is Quito Mariscal Sucre (Berkeley Earth ID: 13263) which has almost 1200 months of data up to the end of 2013 and is located in the capital city, but even it has no data after 2000. And based on evidence from other countries and states, it is reasonable to conclude that the temperature trend for this station is not indicative of the country as a whole (because of its growing urban environment), yet it is the only station with any significant data before 1960. There is a seventh medium station in Ecuador (San Cristobal radiosonde), but that is located in the Galapagos islands over 1000 km to the west and has already been included in my analysis of the South Pacific (see Post 34). For these reasons it will be excluded from this analysis.

Fig. 96.1: The (approximate) locations of the weather stations in Ecuador. Those stations with a high warming trend between 1911 and 2010 are marked in red while those with a cooling or stable trend are marked in blue. Those denoted with squares are stations with over 480 months of data, while diamonds denote stations with more than 240 months of data.

Instead I have also included an additional ten stations with over 240 months of data, even though I generally feel that stations with less than 360 months of data generally add little to the overall trend. The locations of these and the six medium stations are shown on the map in Fig. 96.1 above (see here for a list of all stations with links to their original data). While these stations are fairly evenly distributed, it can be seen that almost all are in the western half of the country on the Pacific side of the Andes ridge. This, though does not seem to be a major issue as will be demonstrated in the analysis below. What is a major issue is the quantity and length of each dataset.

The result of averaging the monthly temperature anomalies from all the stations in Ecuador with over 240 months of data results in the set of mean temperature anomalies (MTA) shown in Fig. 96.2 below. The anomalies for each station were determined by first calculating the twelve monthly reference temperatures (MRT) for each station. The method for calculating the MRTs, and then the anomalies for each station dataset has been described previously in Post 47. In this case the time interval used to determine the MRTs was 1961-1990 as almost all the stations had at least 40% data coverage in this interval. The MRTs for each station were then subtracted from the station's raw temperature data to produce the anomalies for that station. These were then averaged to obtain the MTA for each month.

Fig. 96.2: The mean temperature change for Ecuador relative to the 1961-1990 monthly averages. The best fit is applied to the monthly mean data from 1901 to 2010 and has a positive gradient of +0.98 ± 0.08 °C per century.

The MTA data in Fig. 99.2 clearly shows a positive temperature trend over time that equates to a warming of about 1.0°C over the last century. However, within this trend are fluctuations in the 5-year moving average (yellow curve) that are even greater than the overall rise in the trend (red curve).

One of the principal causes of these fluctuations are El Niño events. These result in large positive spikes in the regional temperature, the most dramatic of which can be seen in 1957, 1972, 1982, 1987 and 1997. The events between 1982 and 1997 in particular appear to contribute significantly to the overall warming trend for Ecuador by leading to a consistent elevated warming in this period. However, after 1997 there is a clear reversal of this with a major dip in temperatures occurring. This appears to correspond to a major La Niña event where the region undergoes a sharp cooling.

Yet curiously something else happens to the data in this period: a lot of it (~75%) appears to go missing. This can be seen in the graph below in Fig. 96.3 which shows the number of stations used to calculate the MTA for each month. Between 2001 and 2008 up to 75% of stations used to calculate the MTA suddenly have no data, just at the point where the mean temperatures of some of the few stations that do have data show a decline in their mean monthly temperatures of up to 4°C.

Fig. 96.3: The number of station records included each month in the mean temperature anomaly (MTA) trend for Ecuador in Fig. 96.2.

The station frequency data in Fig. 96.3 illustrates another deficiency in the data: the lack of it before 1960. In fact, as I pointed out at the start of this post, there is only one station with data pre-1960. Consequently it is plausible to assume that the trend seen in the data before 1960 will differ significantly from that thereafter. The best fit line in Fig. 96.4 below confirms this.

Fig. 96.4: The mean temperature change for Ecuador relative to the 1961-1990 monthly averages. The best fit is applied to the monthly mean data from 1961 to 2010 and has a positive gradient of +0.68 ± 0.17 °C per century.

The result of this is that we cannot with any certainty proclaim what the real temperature trend is. It could be that the climate is warming at over 1°C per century as the data fit in Fig. 96.2 suggests, or it could be less than 0.7°C as indicated in Fig. 96.4 above. And given the severity and frequency of El Niño and La Niña events in the period after 1950, it could be that the real underlying climate variation is even lower. Frankly, we just can't tell.

One way to resolve this might be to compare the temperature data for Ecuador with that of its neighbours. Yet in the previous post (Post 95) I showed that there has been no warming in Colombia since 1940 while in Post 63 I showed that the same was probably true for Peru as well (see Fig. 63.5 in Post 65).

Fig. 96.5: Temperature trends for Ecuador based on Berkeley Earth adjusted data. The average is for anomalies from all stations with over 240 months of data. The best fit linear trend line (in red) is for the period 1901-2010 and has a gradient of +1.06 ± 0.03°C/century.

So how does this tally with the data presented by Berkeley Earth (BE)? Well averaging the BE adjusted data for each station yields the time series for the mean temperature shown in Fig. 96.5 above. This has a warming trend that is significantly larger than that determined using raw data and shown in Fig. 96.2. It is, however, almost identical to the BE published version shown in Fig. 96.6 below even though the official BE trend in Fig. 96.6 is constructed using a mixture of homogenization and station weighting, and incorporates data from stations with less than 240 months of data.

The similarity of the data in Fig. 96.5 and Fig. 96.6 suggests that statistical techniques such as homogenization and station weighting have little influence on the overall trend in this case. That also means that these statistical techniques cannot account for the differences between the trend based on adjusted data in Fig. 96.5 and Fig. 96.6 and the trend resulting from an average of anomalies based on the raw data shown in Fig. 96.2. This difference can therefore only result from the temperature adjustments.

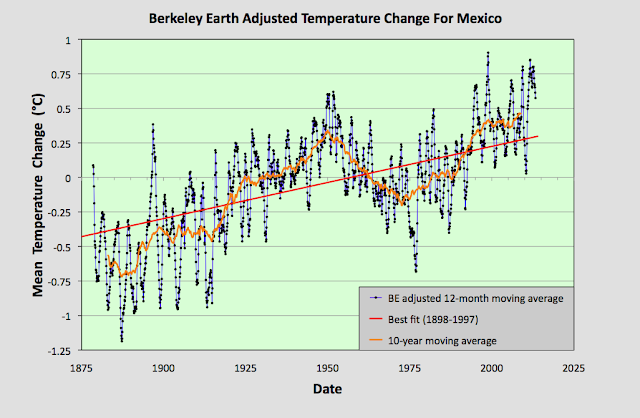

Fig. 96.6: The temperature trend for Ecuador since 1860 according to Berkeley Earth.

So what can we conclude about the overall trend in temperature for Ecuador? The lack of data before 1960 invalidates the trend before 1960 from the discussion, while the lack of data for the period 2001-2008 probably does likewise. The remaining data in Fig. 96.4 after 1960 also fluctuates too greatly for an accurate trend to be discerned, but suggests that the real trend could be anything between zero and 1.0°C per century. Another way to estimate the likely temperature trend might be to compare it with the trend in neighbouring countries. As Colombia (Post 95) and Peru (Post 63) appear to show no evidence of warming after 1940 it would be reasonable to assume that the same is true for Ecuador.

Acronyms

BE = Berkeley Earth.

MRT = monthly reference temperature (see Post 47).

MTA = mean temperature anomaly.